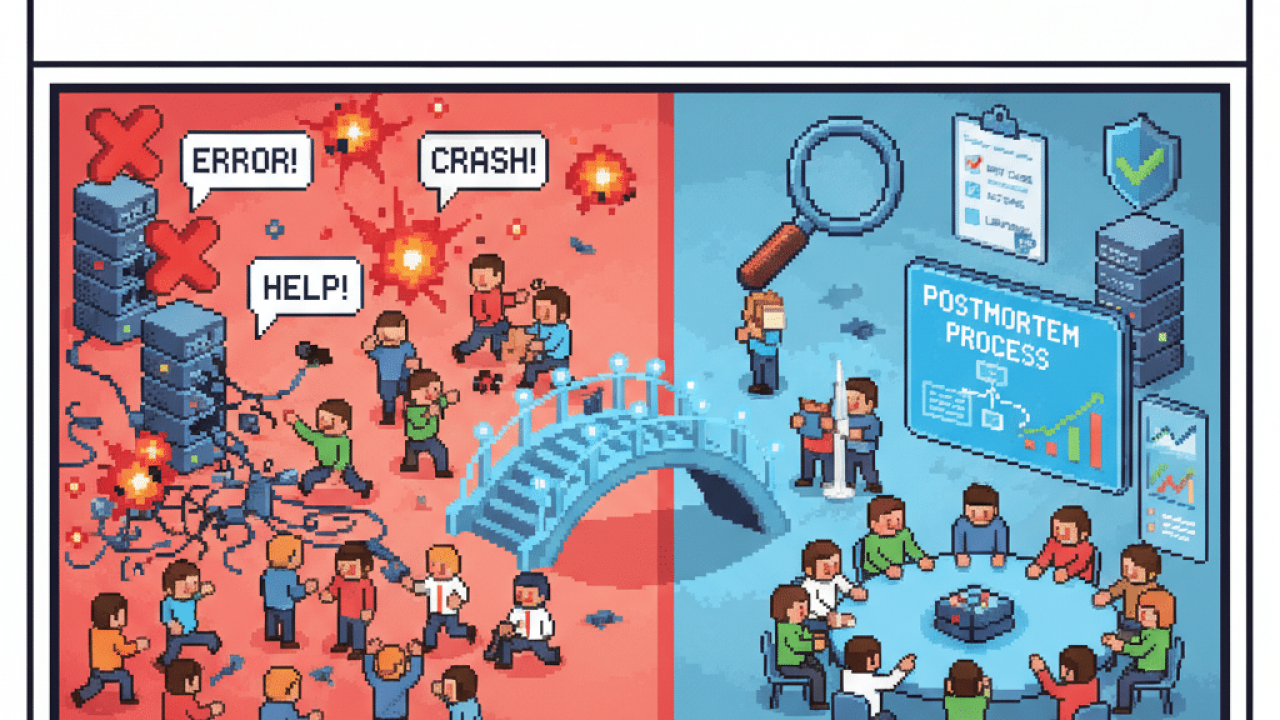

When the engineering team is small, dealing with production incidents usually feels simple. A few people who know the system well jump on a call, figure out what’s wrong, and deploy a fix. The process is fast, loosely structured, and relies on the experience of whoever is there. This works for a while. But as the system becomes more complex and the team grows, this model starts to break down. The same few people keep getting called to fix everything, become a bottleneck, and the knowledge of how to solve problems stays concentrated with them instead of spreading across the team.

Over time, this model stops working. What used to be a quick fix turns into a prolonged crisis, and the pressure on those few people grows until it becomes unsustainable.

The new reality of production incidents

When improvised response becomes a bottleneck

At the beginning, everyone on the team understands how the system works as a whole. When something goes wrong, it’s easy to bring the right people together, because the “right people” are basically everyone. But as you scale, responsibilities get split across multiple teams, and the system becomes a collection of many services that depend on each other. No one understands the full picture anymore.

The burden of resolving incidents keeps falling on the small group of engineers with the deepest history in the system, even when the problem isn’t directly in their area. This concentrates pressure on the most experienced people, accelerates burnout, and makes it harder for other engineers to gain the experience they need to handle these situations. Over time, incident response times increase, because everything depends on the availability of those few people.

When the postmortem loses its value

After the immediate fire is put out, the next casualty is usually the learning process. At first, a postmortem is an opportunity for the team to learn. As incidents become more frequent, poorly structured postmortems turn into just another obligation. The meeting happens, a document is created, but the “action items” are vague, with no clear owners or deadlines.

These documents get archived and are rarely revisited. The same underlying problems resurface months later, creating a frustrating sense of déjà vu across the team. Without a structured process to analyze what happened and generate concrete tasks, with clear ownership, you lose the chance to make systemic improvements and are doomed to solve the same problems over and over again.

From firefighting to preventing fires

When removing blame is not enough

The idea of “blameless postmortems” is a great starting point, but it doesn’t solve everything. Reducing individual blame is important for team well-being, but on its own, it doesn’t create real learning. What makes the difference is turning each incident into a concrete opportunity to improve the system, understanding what failed, why it failed, and which practical changes will prevent the same problem from happening again.

This means shortening the path between fixing an incident and preventing its recurrence. A good postmortem is not just about documenting what happened, but about defining clear changes to the system. It needs to produce concrete actions that make this type of failure increasingly unlikely.

When incidents turn into technical debt

When you fail to act on the lessons of a failure, you are, in practice, accumulating a specific and dangerous kind of technical debt. Recurring incidents caused by the same architectural or process problem are a clear signal that something structural is wrong. Every time one of these problems repeats, customer trust erodes and team morale takes a hit.

Engineers get tired of putting out the same fires, and the unpredictable nature of these outages makes it impossible to plan long-term work. Your engineering capacity gets consumed by reactive fixes instead of being invested in building new features or paying down other forms of technical debt.

How to scale incident response and learning

Defining Clear Roles and Communication Protocols for Production Incidents

The first step to managing this chaos is to create structure. Implementing an Incident Commander (IC) model is one of the most effective ways to do this. The IC doesn’t necessarily write code or deploy fixes; their role is to coordinate the response, manage communication, and ensure everyone involved has what they need. This frees up the other engineers to focus fully on diagnosing and solving the problem.

This structure should also include:

- Dedicated support roles: Have someone responsible for real-time documentation (a scribe or timeline keeper) and another person managing communication with stakeholders. This keeps everyone informed without distracting the engineers doing the hands-on work.

- Layered communication: Establish clear communication protocols. The technical team in the “war room” needs constant, real-time updates. Your customer support team needs clear, non-technical language to share with users. Leadership needs periodic summaries about impact and estimated time to resolution.

How to structure good postmortems

For postmortems to be more than a formality, they need to follow a clear and consistent structure. The goal is to go beyond a simple “root cause analysis” and identify the multiple contributing factors and preconditions that allowed the incident to happen. A single root cause rarely tells the full story.

For a postmortem to generate value, it needs to have:

- A standardized timeline: Start by building a detailed timeline, with timestamps, of events. This includes everything from the first alert, through key discoveries, communication milestones, and finally the resolution. This objective record is the foundation for the entire analysis.

- Focus on contributing factors: Go beyond the search for a single “root cause” and analyze the set of factors that made the failure possible. Investigate which conditions were present, which assumptions about the system turned out to be wrong, and where the process left gaps.

- Actionable and measurable follow-ups: Every action needs to be concrete, with a defined owner and deadline. Vague ideas don’t create change. “Improve database monitoring” doesn’t say what to do or when. But “add alerts for p99 query latency in the user database, owned by the platform team and due by next sprint” makes it clear what needs to happen.

Integrating Incident Learnings into Your Engineering Cycle

The last and most critical piece is ensuring that the learnings from an incident actually feed back into your development process. The output of a postmortem is useless if it just sits in a folder.

You need to create explicit mechanisms to turn those learnings into action:

- Allocate dedicated engineering time: Reserve a portion of each team’s capacity (for example, 10–20% per sprint) to handle incident follow-ups. If this space isn’t planned, these actions always get pushed aside by new features.

- Build a knowledge base: Maintain a central, easy-to-search repository of postmortems and playbooks. When a similar problem comes up in the future, the team already has a clear starting point for investigation. This spreads operational knowledge across everyone and helps avoid knowledge silos.

- Leverage incident data for planning: Use the data and trends from your incidents to guide your technical roadmap. A pattern of recurring database-related outages is strong evidence that you need to invest in a larger architectural improvement project. Repeated database outages, for example, are a clear sign that it’s worth investing in structural improvements. This data helps justify long-term reliability projects and shows the value of using engineering metrics to support decisions