When an engineering team grows from five to fifteen, the informal communication channels that once worked perfectly start to break down. A pull request that used to get three insightful comments now gets a quick approval from someone who lacks deep context. Questions that were once answered by anyone on the team now get routed to a single person. This is the first sign that knowledge is starting to concentrate, creating hidden risks for growing engineering teams.

The problem isn’t specialization itself. It’s good that someone on the team deeply understands the payment processing service.

The problem is when they are the only one.

This creates single points of failure that go beyond the obvious “what if they go on vacation?” risk. It slows down development, makes onboarding new hires a painful process, and quietly lowers the quality bar for large parts of the codebase.

The Real Cost of Knowledge Silos

When critical knowledge is stuck in one or two people’s heads, the rest of the team starts to work around them. This creates bottlenecks that are often hard to spot on a project plan but are felt every day in the development cycle.

Bottlenecks and Single Points of Failure

You can spot this problem in your daily workflow.

– Is there a specific part of the system where PRs always take days longer to get reviewed?

– Is there a developer whose name is on 90% of the commits for a critical service? When that person gets sick or takes a week off, all related work grinds to a halt.

This isn’t just a resourcing issue, it’s a system design flaw in your team’s knowledge architecture. The team loses its ability to respond to incidents or ship features in that area, making planning and forecasting unreliable.

Why Everyone’s Learning Slows Down

In a siloed environment, developers without specific expertise tend to stay in their lane. They avoid picking up tasks in unfamiliar parts of the code because they know the review process will be slow and painful, blocked by the one person with all the context. This discourages curiosity and exploration.

Over time, this makes people avoid those areas even more. No one feels comfortable touching or suggesting improvements to code that “isn’t theirs.” The team’s learning starts to stall, even as new people join.

Onboarding Takes Longer and Agility Suffers

New hires have a much harder time getting up to speed when all the critical context lives in a few individuals’ heads. They can’t just read the code or the docs to understand why a system was built a certain way. They have to find the right person and hope they have time to explain it. This makes your team less agile. You can’t easily swarm on a critical project or reassign people to new priorities because the overhead of knowledge transfer is too high.

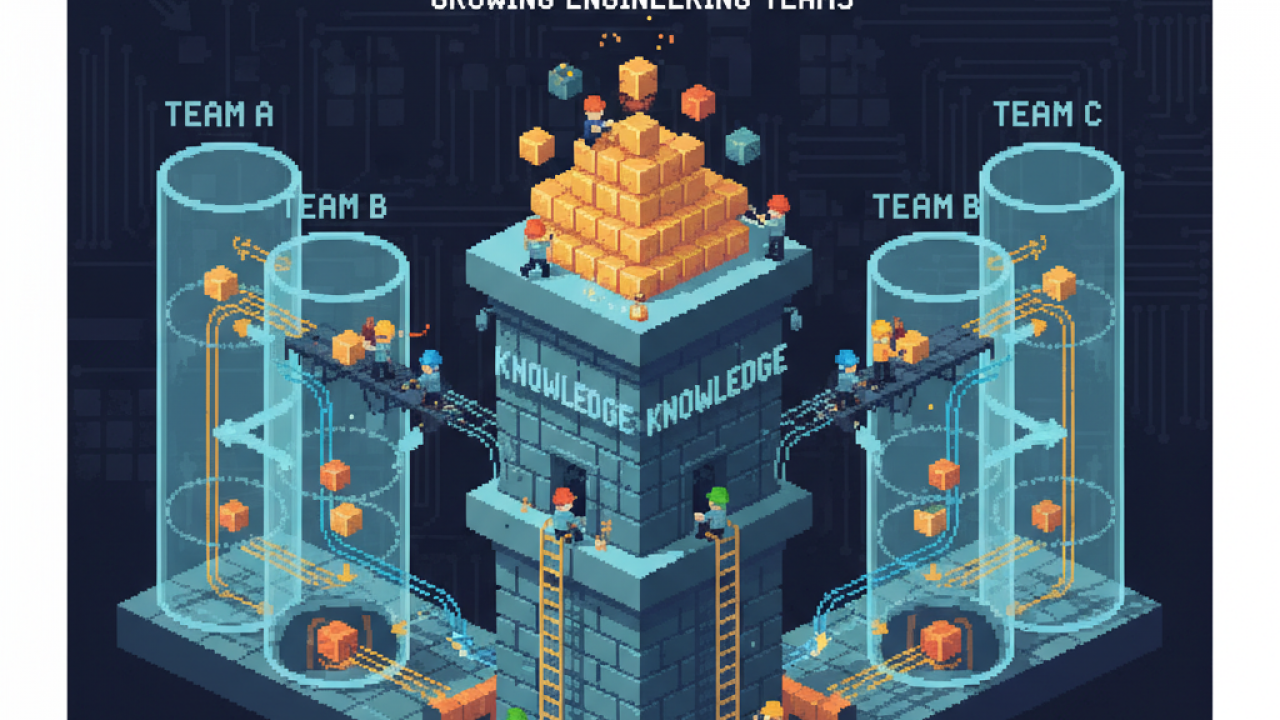

Knowledge Distribution Needs to Be an Active Process

We often assume knowledge spreads naturally, just by working near each other. But as teams grow and codebases get more complex, the opposite happens. The knowledge becomes concentrated in a single person. You have to build explicit practices to pump it through the team, otherwise, you end up with a few overloaded experts and a lot of dependencies.

Why Documentation Alone Is Never Enough

Writing documentation is important, but it’s rarely sufficient. Docs quickly go out of date, and they often miss the “why” behind technical decisions. The most valuable knowledge is the context that’s shared during a design review or a debugging session. A wiki can tell you how a service works, but it can’t tell you about the three failed approaches that were tried before landing on the current one.

Relying on documentation alone often leads to a false sense of security while tribal knowledge becomes more entrenched.

From “Who Knows What” to “How We Learn Together”

The goal is to shift the team’s operating model. Instead of relying on a human index of experts, you build a system where learning is a continuous and expected part of the job. The question is no longer “Who do I ask about the auth service?” but rather “What’s the process for me to learn what I need to know about the auth service?” This makes the whole team more resilient and capable.

Strategies for Building a Resilient Knowledge Culture

Breaking down silos requires intentional, consistent effort. There isn’t a single solution, but a combination of practices that reinforce each other. The focus should be on creating opportunities for context to be shared as a natural part of the development workflow.

Distributing knowledge through pairing and rotations

The most effective way to transfer deep context is to have people work together on real problems.

Structured Pair Programming

This isn’t just about writing code together. It’s about pairing an expert with a novice on a specific feature or bug in the expert’s domain. The explicit goal is knowledge transfer, not just closing the ticket faster. The short-term velocity hit is a worthwhile investment in long-term team resilience. A common mistake here is to make pairing optional or unstructured; it needs to be a scheduled, goal-oriented activity.

Short-Term Rotations

Full team rotations are often too disruptive. A more practical approach is to rotate responsibilities. For example, have a rotating “on-call” developer for a specific service. This forces one person each week to learn the operational aspects of a system they don’t normally work on. Another option is a “bug czar” rotation, where someone is responsible for triaging and fixing bugs in a specific component for a sprint.

Creating spaces for the team to share knowledge

It’s possible to encourage knowledge sharing without turning it into something forced or process-heavy.

Tech Talks and Brown Bags

They work well to give a general overview, but the real value is in the Q&A. When someone does a deep dive into a system they know well, the questions almost always reveal what wasn’t clear or documented.

Dedicated Channels

Create Slack channels for specific technical domains (e.g., #perf-geeks, #frontend-guild, #security-champions). These become places where specialists can share articles and answer questions, making their expertise accessible to a wider audience.

Architectural Decision Records (ADRs)

An ADR isn’t just a static document. Its value comes from the process of creating it. Writing down a technical decision forces you to articulate the trade-offs and alternatives you considered. The PR for a new ADR is a fantastic learning opportunity for the whole team to debate the approach and understand the “why” behind a decision.

Mentorship Programs Within Engineering Teams

When mentoring is intentional, knowledge starts to circulate more effectively. Instead of just pointing someone to help at the beginning, more experienced engineers stay close to real contributions, providing code review, design feedback, and undocumented context.

Empowering Developers to “Teach Back”

One of the best ways to solidify learning is to teach the material to someone else. Encourage developers who have recently learned a new system to lead a brown bag session on it or to write the “getting started” guide for that component. This not only reinforces their own knowledge but also creates learning materials that are perfectly pitched for a beginner’s perspective, something an expert often struggles to do.

Making These Practices Stick

Introducing these practices is one thing; making them a durable part of your team’s culture is another. It requires buy-in from leadership and a willingness to adapt your approach over time.

Leadership’s Role in Prioritizing This Work

If leadership only measures feature velocity, then any time spent on pairing, documenting, or mentoring will be seen as a cost. Engineering managers and tech leads need to actively champion these activities.

That means allocating time for them in sprint planning and recognizing and rewarding people for spreading their knowledge, not just for shipping code.

How to measure if it’s working

Measuring knowledge sharing isn’t simple, but you can spot some signs over time.

-

Bus factor

How many people on the team can safely handle a P1 incident on each critical service? If the answer is just one person, there’s a problem. It’s worth tracking this number over time. -

Who’s reviewing PRs

Look at the distribution of reviewers and approvers across the codebase. Are PRs for the authentication service always approved by the same person? Healthier teams tend to have a broader distribution of reviewers. -

Onboarding time

How long does it take for a new engineer to deliver their first relevant feature without direct help? When knowledge is more accessible, this time should decrease.

Iterate and adjust

There’s no one-size-fits-all set of practices. The key is to test, observe, and adjust. Maybe formal pair programming is too much for your team, but collaborative reviews for more complex PRs might work well. The important thing is to treat it as a real problem and keep experimenting with solutions that fit your team’s workflow and culture.