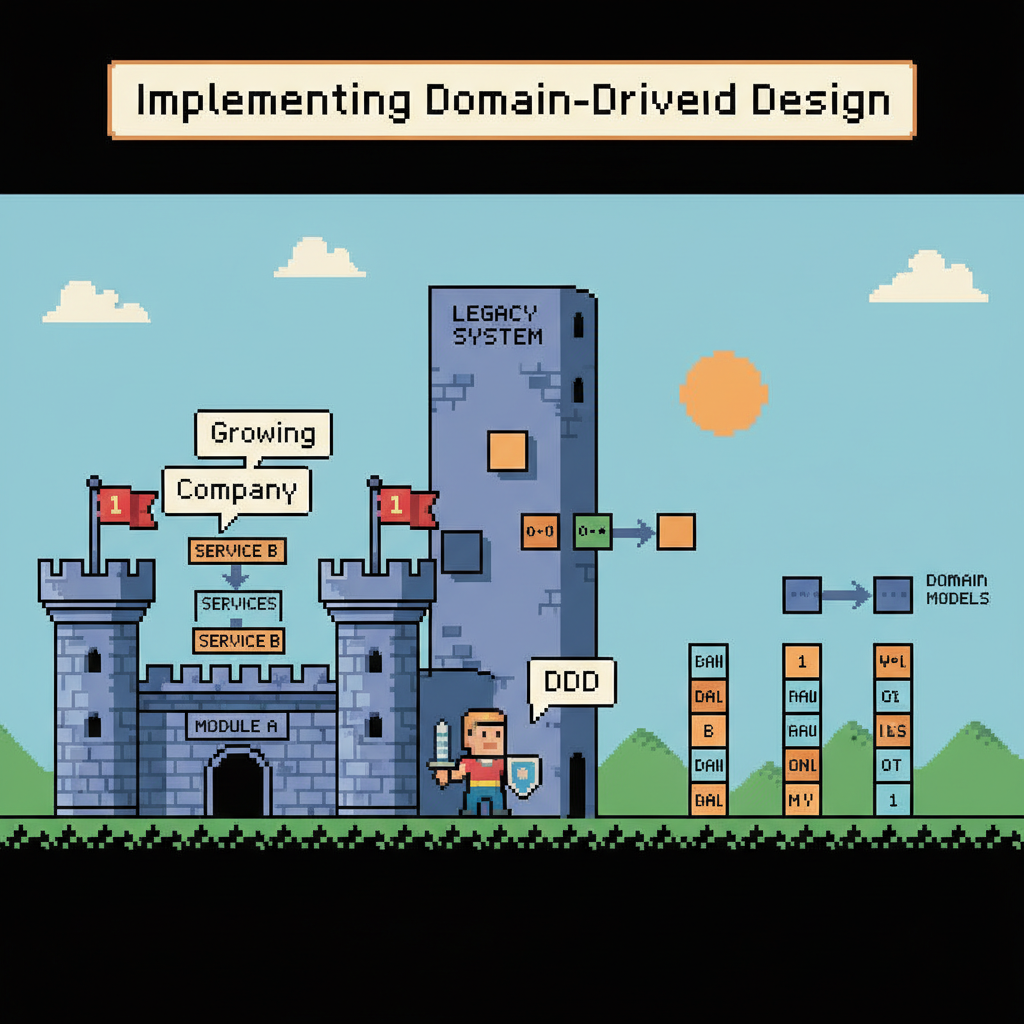

Implementing Domain-Driven Design in a Growing Company

At a certain stage of growth, the codebase stops making intuitive sense. Logic that used to be simple becomes spread across multiple services. A change to the “user profile,” for example, starts affecting five different parts of the system, each with a different definition of what a “user” is. This happens when the original, shared mental model of the software no longer matches the reality of the business it is supposed to support. That is when conversations about the need for a big rewrite start to appear. But the problem is rarely just hard-to-maintain or poorly structured code. The root cause is a growing gap between the structure of the software and the structure of the business. It is exactly this misalignment that Domain-Driven Design tries to address.

The Complexity of Scaling Software

When a company is small, more or less everyone knows how everything works. The business logic lives in the heads of the people who started the team. As new teams are added and new features are delivered, that shared understanding starts to break down. Business rules that used to be common knowledge become implicit, duplicated, or even contradictory when implemented in different parts of the code.

This starts to add weight day after day. The product team gets frustrated because an apparently simple feature request requires a huge engineering effort. Engineers slow down because they need approval from three different teams to make a single change. The cost of this feature-driven growth shows up in ways that are hard to quantify, but easy to feel.

The consequences are practical and hard to ignore:

- Onboarding a new engineer takes months because nothing is where you would expect it to be. You cannot simply point to a single service to understand a business capability.

- Each release carries a high risk of regression. A change in the billing module can break something in analytics because of a dependency that nobody fully understands.

- The ability to respond to market changes slows down dramatically. Pivoting or launching a new product line becomes a major effort, because the existing system is a tangle of interconnected, but logically separate, responsibilities.

When Code Stops Reflecting the Cusiness (and How DDD Helps)

DDD helps close the gap between the software and the business it supports. It shifts the focus away from purely technical concerns, like database schemas and API endpoints, toward modeling the business domain itself. You start by asking “what” and “why” before jumping to the “how.” The goal is for the software to explicitly and usefully reflect the reality of the business behind it.

This forces conversations that should have happened from the start. Instead of an engineer assuming how a “customer discount” works, the team talks to the people who actually understand it, like marketing or sales. These conversations make the real business rules and boundaries clear. A “Product” in the inventory context, for example, is not the same thing as a “Product” in the marketing catalog. Recognizing these differences and modeling them explicitly is at the core of DDD.

Delaying this kind of architectural clarity only makes the problem worse. Each new feature built on top of unclear domain boundaries adds another layer of complexity, making future changes more expensive and slower. You end up with a system that lives in constant conflict with the business it is supposed to enable.

How to Adopt Domain-Driven Design

The good news is that you do not need a six-month project or a complete system freeze to start benefiting from DDD. It can be adopted incrementally, starting with the areas that cause the most pain.

Starting Small by Identifying Your Core Bounded Contexts

The first step is to identify your Bounded Contexts. These are the logical boundaries within the business where a specific model applies. A “Support Ticket” has a clear meaning and a set of rules within the customer support context, but those details are irrelevant to the billing context.

You can uncover these contexts by running collaborative workshops with domain experts from different areas of the company. Look at the code that already exists and map each part to a clear business capability. Which parts of the code deal with shipping? Which deal with user authentication? These slices are usually good starting points. Begin with one or two contexts that are critical to the business and that currently make development slower or more confusing.

Creating a Common Language Across Teams

After identifying a Bounded Context, the most valuable thing you can do is establish a Ubiquitous Language. This is a shared vocabulary of terms that everyone, from engineers to product managers and business stakeholders, agrees on. When an engineer says “Shipment” and a logistics expert says “Shipment,” they are both talking about exactly the same concept, with the same rules and behaviors explicitly defined in code.

This shared language should be used everywhere: in conversations, in documentation, in variable names, and in class names. It removes ambiguity and ensures that the software model accurately reflects the business domain.

Applying Strategic Patterns as the System Evolves

Within a well-defined Bounded Context, you can start applying tactical DDD patterns to reinforce business rules and maintain consistency.

- Aggregates group related objects into a single unit that can be treated as a whole. For example, an

Orderaggregate would containOrderLineItemobjects and would be responsible for enforcing invariants, such as ensuring that it is not possible to add an item to an order that has already been paid. The aggregate root (Order) is the single entry point for modifications, which keeps the model consistent. - Value Objects represent descriptive aspects of the domain that are identified by their value rather than their identity, such as a

MoneyorAddressobject.

For existing systems, the Strangler Fig pattern is a way to introduce these concepts incrementally. You can build a new service that correctly models a single Bounded Context and gradually redirect calls from the old monolith to this new service. Over time, it becomes possible to safely retire parts of the legacy system, without a risky “big bang” rewrite.

This process works best when it is iterative and team-driven. Give a single cross-functional team ownership over a domain end to end. They become the experts and have the autonomy to model it correctly based on feedback from domain specialists.

A Checklist for Your First Steps with DDD

- Start a discovery phase. Run a session with engineers and product people to map the most painful areas of the codebase and identify potential domain boundaries.

- Form a small cross-functional team around what appears to be a single Bounded Context. Include a domain expert from the business side if possible.

- Define and document your initial Ubiquitous Language terms. Start a shared document with the first 5 to 10 core terms of the chosen context and make sure everyone agrees on their precise meaning.

- Identify at least one Aggregate root in the chosen context and map its invariants (the business rules it must always protect).

- Plan incremental changes. Use a pattern like Strangler Fig to build a small, well-modeled piece of functionality that can replace a slice of the old system, validating the approach before taking on a larger change.