When to break up a monolith: a guide to adopting microservices

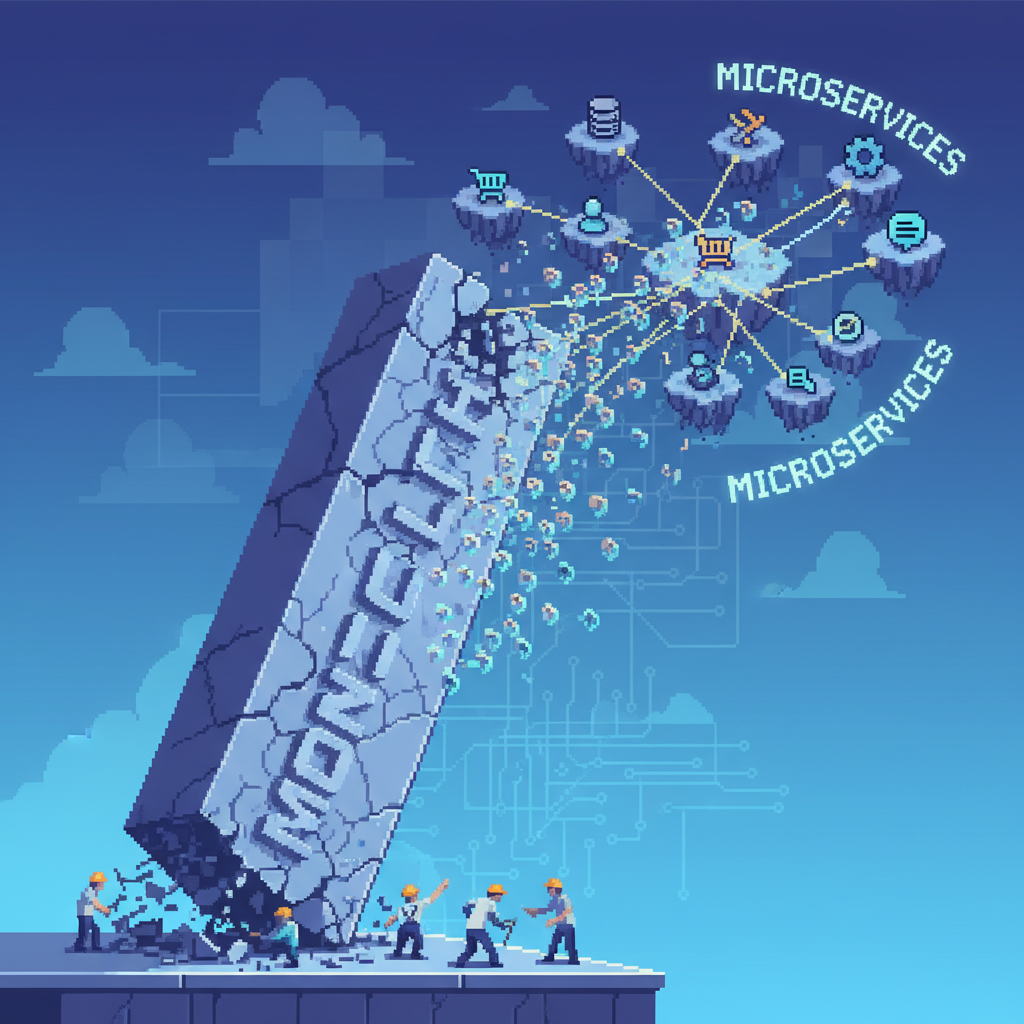

The conversation about moving from a monolith to microservices usually starts when things get painful. Builds take forever, a small change requires a full redeployment, and multiple teams are constantly blocked by each other in a single codebase. You can’t scale the user profiles service without also scaling the rarely-used reporting module it’s tied to. The initial simplicity that made the monolith attractive has given way to bottlenecks that slow down product growth.

The monolith isn’t inherently bad; it’s often the most logical starting point. The problem is that as complexity grows, coupling tightens, and making changes becomes slow and risky. Eventually, every deploy feels like a high-stakes event, and technical debt accumulates in corners of the codebase no one has touched for years. This is usually when someone brings up breaking it all apart.

Microservices promise a solution: independent services that can be developed, deployed, and scaled on their own. Teams gain end-to-end ownership of their code, choose the best technology for each problem, and stop depending on large, synchronized deploys across multiple teams. But this flexibility comes with the inherent complexity of distributed systems. Suddenly you’re dealing with network latency, data consistency across services, and a significant increase in operational overhead.

How to know if it’s time to break up the monolith

Moving to microservices is a decision that should be driven by clear business and organizational needs, not just technical appeal. Before you write a single line of code for a new service, you need to assess if your system, your business, and your teams are actually ready for the shift.

Business and Technical Drivers

The most compelling reasons to decompose a monolith are tied to specific pain points.

Are different parts of your application evolving at vastly different rates?

Does one feature require scaling capabilities that are 100x greater than the rest of the system?

These are strong indicators that your architecture is holding you back.

Here are some questions to help identify if you have the right technical drivers:

- Independent Evolution: Do you need to update the checkout process multiple times a week, while the user authentication system changes once a year? If so, decoupling them allows the checkout team to move faster without risking the stability of authentication.

- Divergent Scaling Needs: Does your video processing module need massive compute resources for a few hours a day, while the rest of the app has steady traffic? Separating it allows you to scale that service independently, saving on infrastructure costs.

- Technology Requirements: Is there a part of your system that would benefit greatly from a different programming language or database? A data science component might be better suited for Python and a specialized database, which is hard to integrate into a monolithic Java or Ruby application.

Organizational Readiness

This is where most teams get it wrong. You can have the perfect technical reasons for adopting microservices, but if your organization isn’t set up for it, you will likely create a distributed monolith, which is far worse than what you started with.

A few points help determine whether the organization is ready:

- DevOps Maturity: You need fully automated, reliable CI/CD pipelines. If deploying is a manual, multi-step process, managing dozens of services will be impossible. Each service should have its own pipeline that can deploy to production independently.

- Observability: In a monolith, a stack trace tells you most of what you need to know. In a distributed system, a single request might traverse multiple services. Without centralized logging, distributed tracing, and robust metrics, debugging becomes a nightmare. This infrastructure needs to be in place from day one.

- Team Structure and Expertise: Your teams need to be equipped to handle the complexities of distributed systems. This means having expertise in things like containerization (like Kubernetes), API design, and network communication. You also need clear API governance to ensure services can communicate effectively without creating tight coupling.

A practical guide to breaking up the monolith

Once you’ve decided to proceed, the migration itself should be a gradual, incremental process. A “big bang” rewrite is almost always a mistake. The goal is to safely carve out pieces of the monolith without disrupting the existing system.

Finding Service Boundaries with Domain-Driven Design

The first step is figuring out where to draw the lines between your new services. This is more of an art than a science, but Domain-Driven Design (DDD) provides a useful framework. The key concept here is the “Bounded Context,” which is a boundary within which a particular domain model is consistent and well-defined.

In practice, this means looking for logical domains within the application. An e-commerce system might have bounded contexts such as “Orders,” “Inventory,” “Payments,” and “User Accounts.” Each of these is a good candidate to become a separate microservice because its internal logic and data are relatively independent.

Incremental Migration with the Strangler Fig Pattern

The Strangler Fig Pattern is the most reliable way to perform an incremental migration. The idea is to build a new service and gradually “strangle” the old monolith by routing traffic to the new implementation until the old one can be retired.

It typically works like this:

- Set up a proxy layer: An API Gateway or another proxy is placed in front of the monolith. Initially, it just passes all traffic through to the old system.

- Extract a service: You identify a piece of functionality, like user profile management, and build it as a new, independent service.

- Redirect traffic: You configure the proxy to route all requests related to user profiles (e.g.,

/api/users/*) to the new service. All other traffic continues to go to the monolith. - Repeat: You continue this process, extracting one service at a time, until the monolith has been fully replaced or shrunk down to a manageable core.

An “anti-corruption layer” is often implemented alongside this pattern to act as a translation layer between the new service’s model and the old monolith’s model, preventing the legacy design from leaking into your new architecture.

Data Management is the Hardest Part

Decomposing the code is one thing; decomposing the database is another entirely and is often the biggest challenge. The ideal state is the “database-per-service” pattern, where each microservice owns its own data and other services can only access it through a well-defined API. This enforces true decoupling.

Getting there requires a phased data migration strategy. You might start by having the new service write to its own database but read from the monolith’s database. Over time, you can implement mechanisms to synchronize data until the new service becomes the single source of truth and the old tables can be removed.

For operations that span multiple services, you can’t rely on traditional ACID transactions. This is where patterns like the Saga Pattern come in. A saga is a sequence of local transactions where each transaction updates the database in a single service and publishes an event that triggers the next step in the process. If a step fails, the saga executes compensating transactions to undo the preceding steps, maintaining data consistency.

Preparing teams for a distributed system

You can’t build a distributed system with a centralized team structure. Conway’s Law states that organizations design systems that mirror their communication structures. To build loosely coupled services, you need loosely coupled teams.

This often requires applying the “Inverse Conway Maneuver”: restructuring your teams to reflect the architecture you want. This means creating small, autonomous, cross-functional teams that have end-to-end ownership of a service or a set of related services. This team is responsible for everything: development, testing, deployment, and on-call support. Empowering teams with this level of ownership is critical for the success of a microservices architecture.

What usually goes wrong

The path to microservices has several pitfalls. Knowing where they are helps you avoid problems along the way.

Starting too early

Don’t decompose before you have to. If your monolith is manageable and your team can ship features effectively, stick with it. The overhead of microservices is substantial.

Making services too small

The goal is not to create as many services as possible. “Nanoservices” can lead to an explosion of operational complexity and network chatter. Start with larger, domain-aligned services and only break them down further if there’s a clear need.

Underestimating observability

If you wait to implement proper monitoring and tracing until after your services are in production, you’re going to have a bad time. Build observability in from the beginning.

Creating a distributed monolith

This is the worst of all outcomes. It happens when your services are tightly coupled through synchronous calls or a shared database. A failure in one service can cascade and take down the entire system, and deployments still require coordinating multiple teams. The key is to design for loose coupling and asynchronous communication wherever possible.

Ultimately, moving to microservices is a long-term investment. It’s not a quick fix for a messy codebase. When done for the right reasons and with a solid foundation of infrastructure and team practices, it can provide the scalability and development velocity needed to support a growing product. But if you jump in without a clear plan, you risk trading a familiar set of problems for a much more complex and distributed one.