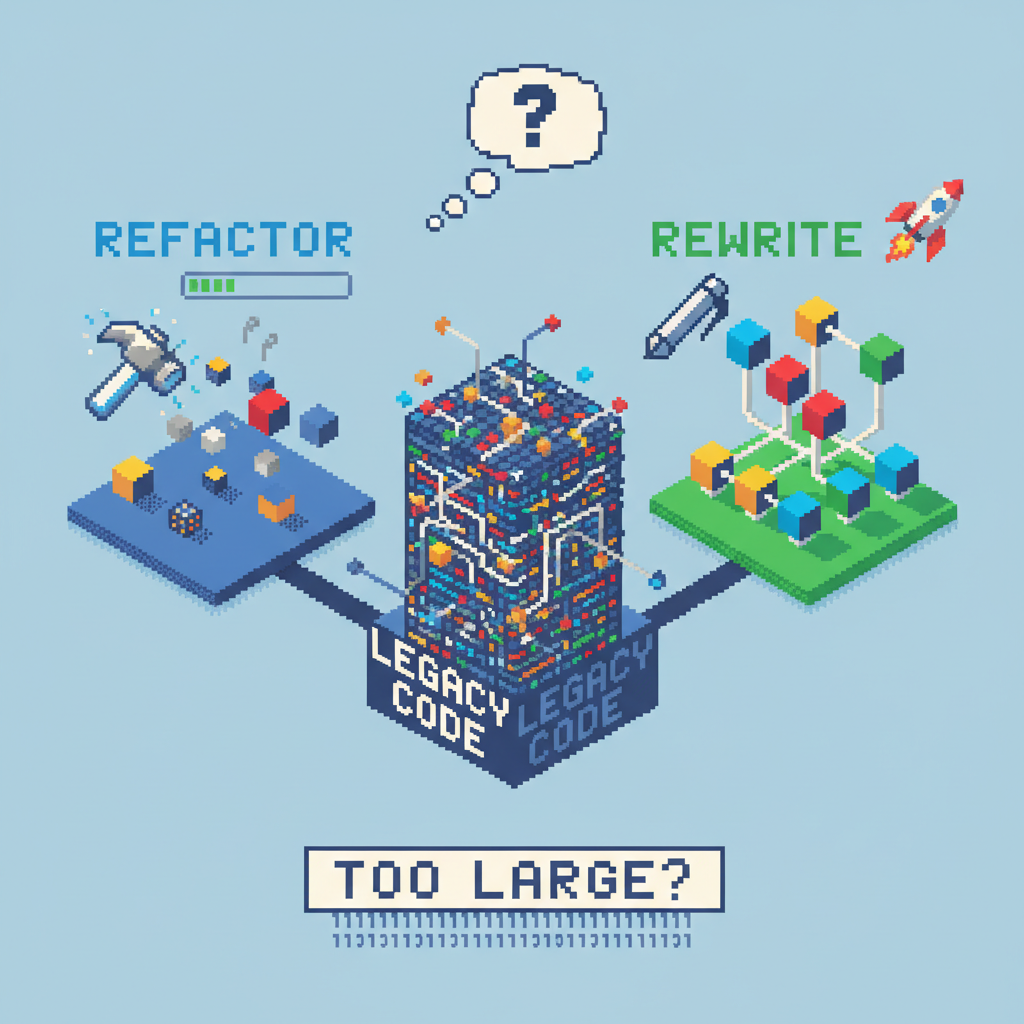

Refactor or Rewrite? Dealing With Code That’s Grown Too Large

The decision to refactor or rewrite a large codebase usually starts with a feeling of friction. Small changes that should take a day suddenly take a week. Every new feature seems to break an old one, and the team’s bug backlog grows faster than it shrinks.

This happens because systems don’t just age, they accumulate history. Every feature request, urgent fix, and change in direction adds another layer of code. Over time, what was once a clean architecture turns into a web of dependencies and workarounds. The pressure to ship new features means there’s rarely time to go back and clean things up, so technical debt piles up. When you reach this point, the system starts actively resisting change, and every pull request becomes a painful negotiation with the past.

Signs the system is at its limit

It’s easy to complain about a codebase, but there are clear signs that a system is close to breaking. The most obvious one is a steady drop in development speed. You can measure this with cycle time or, more simply, by comparing how long it takes to ship a basic feature today versus a year ago.

Another clear sign is an increase in regressions in specific parts of the system. When fixing one bug almost always creates another, it usually points to an architecture that’s too tightly coupled, where small changes have side effects that are hard to predict.

There are also human costs. When engineers spend more time fighting the system’s limitations than building with it, motivation drops fast. Onboarding new people becomes hard because the cognitive load required to understand the system is huge. And when your most experienced engineers start asking to work on anything else, or you struggle to hire because no one wants to touch the “legacy” stack, that’s usually a sign the system has reached a critical point.

Accidental complexity vs. essential complexity

Before making a good decision, you need to understand what kind of complexity you’re actually dealing with. Software complexity usually falls into two groups: essential and accidental.

Essential complexity is inherent to the business problem you’re solving. If you’re building a payment processing system, you have to deal with regulations, fraud detection, and multiple payment gateways. No matter how clean the code is, that complexity doesn’t go away. The best you can do is keep it under control.

Accidental complexity, on the other hand, comes from the choices we’ve made along the way. It’s the result of outdated libraries, poorly designed abstractions, inconsistent patterns, or quick fixes that were never revisited. This is the complexity that makes code hard to read, test, and change, even when the business logic itself is simple.

Why this distinction is everything

This distinction is the most important factor in the refactor versus rewrite debate.

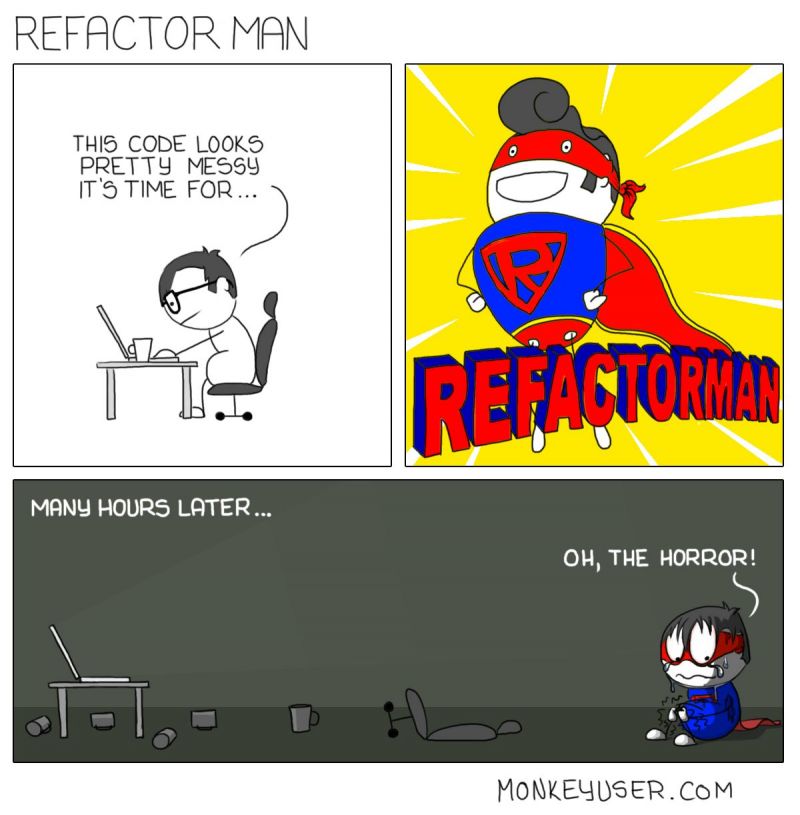

Refactoring is an excellent tool for attacking accidental complexity. It helps improve abstractions, simplify parts of the system that no longer make sense, and make the codebase more consistent, which makes day-to-day work easier. If your problem is mostly accidental complexity, a series of targeted refactorings is almost always the right answer.

A full rewrite, however, is often proposed as a solution to all complexity. The problem is that a rewrite doesn’t remove essential complexity.

If the team doesn’t deeply understand the business domain and its inherent challenges, they’ll simply recreate the same essential complexity in a new language or framework, only now without years of bug fixes and edge-case handling baked in.

That’s why so many rewrites fail. They confuse essential complexity with accidental problems and end up producing a new system with the same issues as before, plus several new ones.

What are the costs of refactoring or rewriting?

Both refactoring and rewriting come with costs that go far beyond engineering hours, and they’re often underestimated.

The price of refactoring

The most significant cost of refactoring is opportunity cost. Every hour your team spends on internal improvements is an hour not spent on customer-facing features. This can be a hard sell to product and business leaders who don’t see immediate value. On top of that, a large refactoring effort sometimes fails to deliver the promised benefits if it doesn’t address the real architectural problems.

You can spend months cleaning up modules only to realize that the real issue is how the database is structured or how services communicate.

The problem with a full rewrite

A full rewrite is one of the riskiest projects a software team can take on. Timelines are almost always wildly optimistic. While the new system is being built, the old one still needs to be maintained, which means running two systems in parallel and splitting the team’s focus. All the unwritten rules and implicit knowledge about why the old system works the way it does get lost, leading to a new wave of bugs and regressions.

This often leads to what’s known as the “second system effect.” Free from the constraints of the old system, architects try to build a perfect, overengineered solution that solves every problem they can think of. Scope grows out of control, the project drags on for years, and by the time it’s finally ready, the business needs have changed again.

When should you refactor or rewrite?

Instead of relying on gut instinct, you need a structured way to evaluate your options. The decision should be based on a clear analysis of the trade-offs.

Criteria to evaluate your options

Here are a few key areas to assess with the team:

Technical viability

Being realistic, can the current system be maintained for the next two or three years? Or are there architectural decisions, like a monolith that blocks teams, that refactoring won’t fix?

Risk to business continuity

What can go wrong with each option? Refactoring too aggressively can create production instability. Rewriting everything introduces a different kind of risk, with many unknowns and a long, delicate migration.

Team capacity and knowledge

Does the team have the skills to execute a rewrite in a new technology? Just as important: is there enough knowledge about the quirks of the old system to avoid repeating past mistakes?

Total cost of ownership

Look beyond the initial project cost. Consider long-term maintenance costs, the cost of running systems in parallel during a rewrite, and the impact on hiring and retention.

A simple heuristic

If you need a simpler way to look at the decision, compare the estimated cost of incrementally refactoring the existing system to a state that meets future requirements with the total cost of starting from scratch.

Be honest and comprehensive in your estimates, including parallel maintenance, migration, and the operational overhead of a new system.

If the cost of a rewrite is even close to the cost of refactoring, the incremental path is almost always the safer and better choice, because it allows you to deliver value more continuously and manage risk along the way.

How to execute

Once the decision is made, everything depends on execution. Both paths can work, as long as there’s discipline, clear ownership, and a direct connection to business goals.

Incremental refactoring with Strangler Fig

If the decision is to stick with the existing system, improvement needs to be continuous, not a large, one-off project. Make room in every sprint to reduce technical debt and improve what’s already in production.

When larger architectural changes come into play, the Strangler Fig pattern often works well. The idea is simple: pick a specific piece of functionality, implement it as a separate service, and start routing traffic to this new component through a proxy or routing layer. Gradually, parts of the old monolith stop being used and can be removed.

Over time, the legacy system gets replaced in a controlled way, without a big-bang migration. This lets you modernize gradually, keep delivering value, and significantly reduce the risk of breaking something critical along the way.

Phased rewrites with a minimum viable scope

If a rewrite is truly unavoidable, the key is to aggressively limit scope. Define a Minimum Viable Rewrite (MVR) that focuses on a small, well-understood vertical slice of the system.

The goal is to get part of the new system into production as quickly as possible, even if it runs alongside the old one. Use feature flags and canary releases to roll the new system out gradually to users, giving yourself time to find and fix issues before a full cutover. This phased approach turns a huge, high-risk project into a series of smaller, manageable steps.

Governance and long-term alignment

No modernization effort will succeed without clear governance. This might mean setting up an Architecture Review Board to guide technical decisions or implementing automated tools to monitor code quality and technical debt.

More importantly, any refactoring or rewrite initiative needs to be tied to clear product and business goals. If you can’t connect the technical work to real improvements, like faster delivery, greater stability, or a better user experience, support tends to fade over time.