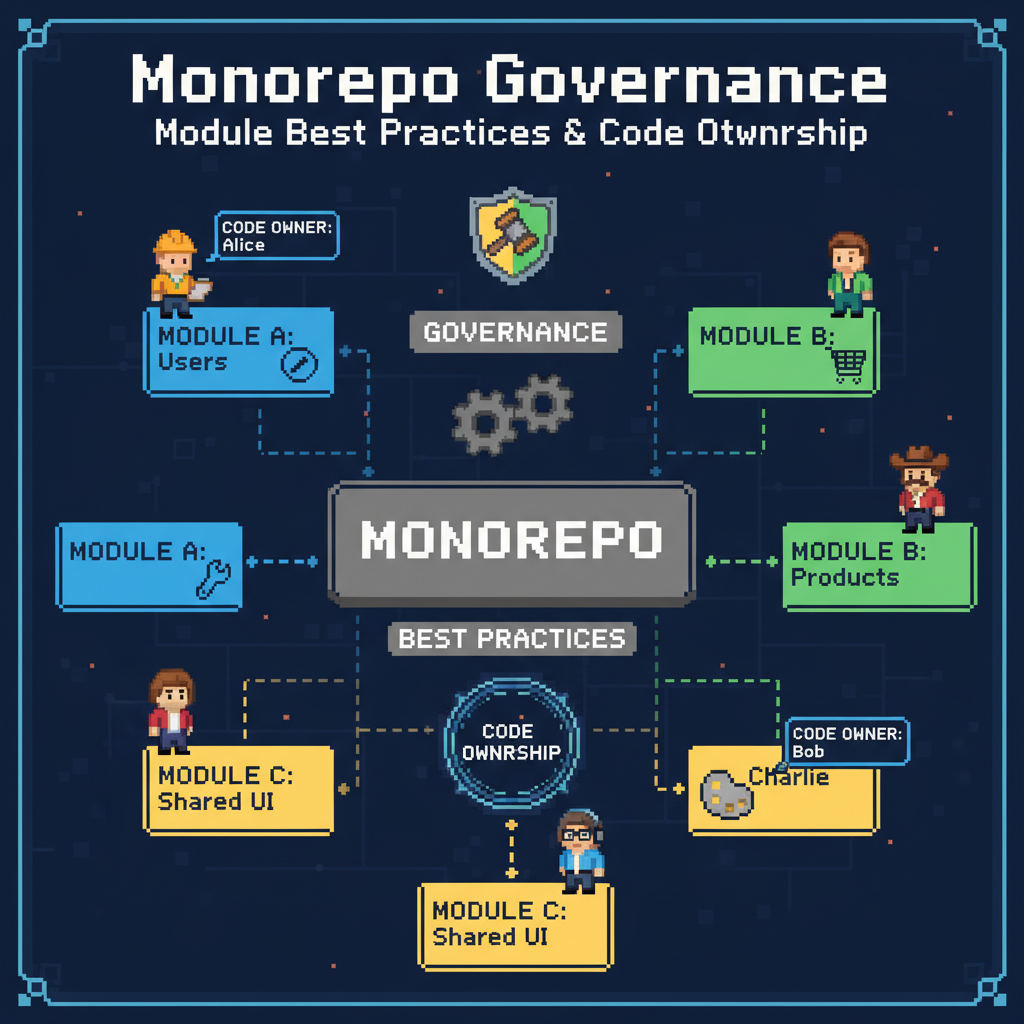

Monorepo governance: module best practices and code ownership

At the beginning, the idea of a monorepo is quite appealing. Having all the code in one place, centralized dependencies, and the ability to change multiple parts of the system at once simplifies a lot of things. This works well while the team is small. As the team grows, however, that simplicity starts to fade. As more teams and engineers begin to contribute, the codebase becomes harder to understand and evolve. When thinking about the best strategy for a growing codebase, this complexity needs to be managed. A change that should be simple requires touching ten different packages, and suddenly your PR has a dozen reviewers from teams you’ve never met. You end up spending more time coordinating changes than writing code.

This happens when a monorepo grows without clear rules. What starts as a shared codebase ends up accumulating hard-to-understand dependencies, without well-defined owners. This often leads to questions about when to break up a monolith. Builds get slower, tests start failing intermittently, and every merge carries a higher risk of side effects. The speed that seemed guaranteed at the beginning simply disappears.

The costs of a monorepo without governance

When a codebase grows without clear boundaries, two problems usually show up at the same time: dependencies out of control and the illusion of shared responsibility. One is a technical problem, the other is a people problem, and they feed into each other.

When dependencies get out of control

Without enforced rules, developers will naturally import code from wherever is most convenient. A utility created in one service starts being used by another, then another. Before long, dependencies spread with no clear limits. The result is coupling that’s hard to understand, changes that affect unexpected areas, and a system that becomes increasingly risky to evolve.

- Difficulty understanding relationships between modules. When you can’t easily see who depends on whom, estimating the impact of a change becomes a huge effort. You end up running the entire test suite for a one-line change, just to be safe.

- Higher risk of unintended side effects. An apparently harmless change in a “shared” module can break a completely unrelated part of the system. This type of bug often reaches production because no one thought to test that specific interaction.

- Slower build and test cycles. Tools help compile and test only what was affected by a change, but they’re not magic. If everything depends on everything, everything needs to be rebuilt and retested every time.

Why “everyone owns it” means no one does

The idea that “everyone owns the code” sounds collaborative, but in a large monorepo it often has the opposite effect. When there is no clear ownership over a module or domain, no one truly feels responsible.

- Review bottlenecks. A PR that touches a critical part of the system, but has no clear owner, often sits idle for days. Everyone recognizes it’s important, but no one feels comfortable making the call and giving final approval.

- Outdated or unmaintained code. Some parts of the codebase end up being neglected. They still work, but no one actively maintains, organizes, or plans their evolution. They become a source of technical debt everyone avoids.

- Onboarding difficulties. New team members struggle to figure out who to talk to about each part of the code. Without clear owners, there are no designated experts to answer questions, which significantly slows down ramp-up time.

Shifting the perspective: modules with well-defined responsibilities

To scale a monorepo without losing control, you need to deliberately introduce structure and responsibility. This goes beyond organizing folders and files. It means treating each logical part of the system as a well-defined module, with clear boundaries and an explicit contract about what it provides and what it depends on.

A module is not just a directory. It’s a component with a well-defined purpose and, more importantly, a clear public interface. Everything else is internal implementation detail that other modules should not be able to access.

This requires a more disciplined approach:

- Explicitly defined public interfaces. Each module should expose a minimal and stable API. This is often done through a single entry file, such as an

index.ts, which exports only what is intended for public consumption. - Strict enforcement of internal structure. No direct access to a module’s internal files. This rule needs to be automatically enforced in CI to prevent accidental dependencies on implementation details that are likely to change.

- Clear versioning or consumption strategies. Even within a monorepo, it’s useful to think about how modules are consumed. When a module’s public API changes, there must be a clear process for downstream consumers to adapt.

This discipline around modules is the foundation. The next layer is assigning clear ownership to each of these modules. Intentional ownership is a prerequisite for gaining speed, because it creates clear lines of communication and responsibility.

Designing a healthy monorepo: practical steps

Establishing clear rules doesn’t need to turn into a heavy, top-down process. You can start small by defining a few code standards and best practices and using automation to make sure they’re followed.

Defining clear boundaries and API contracts

First, you need to identify the logical domains within the codebase. They might correspond to features, services, or shared libraries. Once these domains are mapped, the next step is to encapsulate them into well-defined modules with clear boundaries.

- Design stable and minimal interfaces. The goal of a module’s public API is to be as small as possible while still being useful. The more you expose, the more you have to maintain and the harder it becomes to change later.

- Document responsibilities and usage. Each module should have a

README.mdthat clearly explains what it does, who owns it, and how to use its public API. This is the module’s contract.

How to manage internal dependencies

After defining modules, you need to reinforce the boundaries between them. The goal is to prevent dependencies from spreading out of control again.

- Apply a layered architecture. A common pattern is to define levels such as “application”, “domain”, and “platform”, and enforce rules about which layers can depend on which. For example, application code may depend on platform code, but not the other way around.

- Use automation to check forbidden dependencies. This is non-negotiable. Your CI pipeline must include a step that fails the build if a PR introduces an illegal dependency.

Establishing and reinforcing code ownership

With clear boundaries between modules, it becomes possible to assign owners objectively. Ownership makes it clear who is responsible for the long-term health of a piece of code.

- Choose the right ownership model. Ownership can be assigned to individuals or teams. For shared libraries, a component-based model with a few key maintainers usually works well. For business domains, it often makes more sense for the entire team to own the relevant modules.

- Leverage automation for governance. This is where tools like

CODEOWNERSfiles come in. Use them to automatically route PRs to the right team for review. This ensures that the people with the most context are always involved. You can also integrate linting tools to enforce architectural rules and automate code health metrics, such as complexity or test coverage, for each owned module.

How to maintain a healthy monorepo

Bringing a monorepo back to a healthy state, or keeping it that way, comes down to a consistent set of practices. If you’re looking for where to start, focus on these five rules.

- Define explicit boundaries for all modules. Every logical part of the code should live in a module with a defined public API.

- Assign clear owners to every module. Every file in the repository should have a clear owner specified in a

CODEOWNERSfile. No exceptions. - Implement automated dependency checks. Use CI to automatically enforce your architectural rules and prevent illegal imports between modules.

- Establish a consistent strategy for module evolution. Have a documented process for introducing breaking changes to a module’s public API.

- Create a process for deprecating modules. As important as creating modules is knowing how to retire them. Document how to safely deprecate and remove a module.

A well-governed monorepo allows teams to work autonomously while still benefiting from shared code and infrastructure. It’s not about adding more bureaucracy, but about creating the structure needed to scale development in an efficient way.